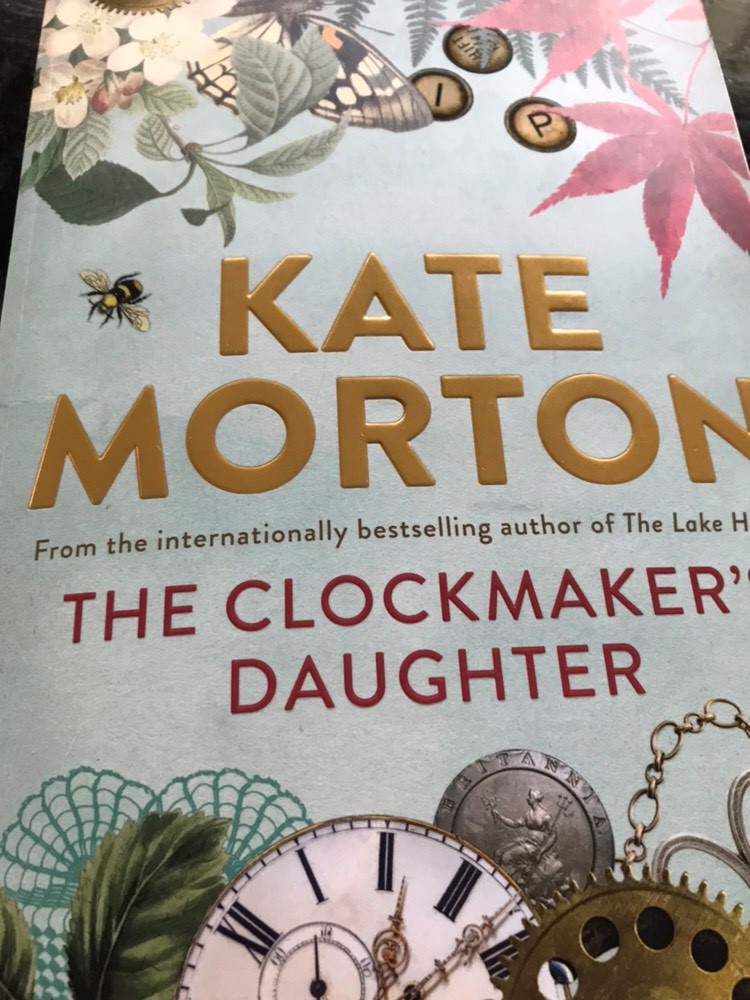

I have always described Kate Morton as a poor man’s A S Byatt. Although her historical mystery stories are as gripping as Possession, the writing is certainly not as good. Nonetheless, she writes engaging storylines with pretty good prose and, as a Brisbane author who has topped the New York Times bestseller list, she warrants some attention.

Unfortunately, I expect most fans will be very disappointed with her latest novel. Like her previous books, The Clockmaker’s Daughter is set in England and covers multiple generations of comings and goings from a grand country home.

It starts with Elodie, an archivist in modern day London, who discovers a satchel belonging to Edward Radcliffe who was a fringe member of a group of talented artists from the 19th Century. In a coincidence of Dickensian proportions, Elodie recognises the house painted by Radcliffe as belonging to a childhood story her mother told her. This is a segue way into one of many families and groups effected by a death at Radcliffe’s home in 1862. The different inhabitants and visitors to the home over the next 150 years are presided over by a ghost.

Unlike Morton’s other books, the story is very slow to get going. I would not have persevered for an unknown author. The supernatural element of the story is poorly conceived and did not add anything to the narrative.

Members of one of my book clubs have complained before about Morton’s tendency to involve too many characters. It has not troubled me in any of her other books but the number of different storylines in this book made the story incoherent at times. None of the characters were developed enough to be engaging.

Another irritation was the tacky literary allusions. The missing blue diamond that used to belong to Marie Antoinette was straight from James Cameron’s Titanic and the names of the characters were an obvious reference to Narnia. Literary allusions are only fun when they are disguised at least a little.

The end of the story was satisfying enough. This made me think of an editor who once told me that she could see when the Harry Potter books stopped being edited. After book 4, the publishers were not game to interfere with any of Rowling’s work for fear of removing the magic and, as a result, the narrative was much less disciplined.

Perhaps that is what has happened with Morton – she has become a victim of her own success.